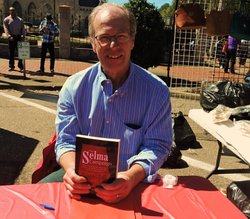

Craig Swanson is retired journalist and editor and author of “The Selma Campaign,” released through Archway Publishing in November 2014. The book examines the impact of the “foot soldiers” in the Civil Rights struggle for voting rights. Swanson and his book were featured in a video on Oprah.com.

When I retired from daily newspapering a few years ago, I tried writing a novel. The results were, to be charitable, uneven. What had once seemed a fairly easy proposition – develop an interesting narrative and present it in lucid and compelling prose – turned daunting.

For years, I was sure that the only thing preventing me from writing The Great American Novel was time – time to massage the story line and brood over character development; time to ponder plot twists and establish just the right tone. Mostly, I just needed time to think, which is what retirement gave me.

Six years, a lot of thinking and three abandoned novels later, I no longer aspire to write a great work of

Craig Swanson stands on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, site of the March 7, 1965, “Bloody Sunday” Civil Rights conflict.

fiction. In fact, I’ve determined that I couldn’t write a good — or even an average — work of fiction. A review of my failed manuscripts suggests that my main problem was story and character development.

Due either to a stunted imagination or, more likely, some 40 years as a daily journalist accustomed to gathering “just the facts,” I was unable to summon the creativity needed to see a novel through from beginning to end. I had some good ideas, but they went nowhere, and I grew frustrated trying to pull them all together.

Interestingly, I also struggled with the simple act of writing. Though I had never lacked confidence in my writing abilities, I found myself questioning virtually everything I typed, afraid much of it would appear either inadequate or overwrought. This wasn’t the old Inverted Pyramid, and I didn’t trust my own instincts enough to move forward.

This novel experience gave me a newfound appreciation for the imagination and creativity needed to produce a fictional work and genuine admiration for those who do it well. It also taught me to stick with what I know best – straightforward nonfiction writing.

I’ve now had two successful books published – non-fiction, both – and while that doesn’t make me an expert on the genre, it has given me some insights that might be helpful to other aspiring authors. Following are a few of the important things I learned while writing “Something in the Air: Rock Music and Cultural Upheaval in Mid-60s America” and “The Selma Campaign: Martin Luther King Jr., Jimmie Lee Jackson, and the Defining Struggle of the Civil Rights Era.”

- Write about what you know. Even though your book will require long hours of research, it’s best to tackle subjects about which you already have a broad working knowledge. Life will be much easier if you embark on your project with at least a general understanding of the history and significance of the issue or event you intend to tackle.

- Write about something that interests you. All the knowledge in the world won’t help unless you are passionate about the story you want to tell. In my case, rock music and the Civil Rights Movement were obvious choices.

- Maintain a narrow focus. It’s tempting to want to be as comprehensive as possible, but unless you have a team of professional researchers, a hefty advance and unlimited time, it’s also unrealistic. For me, that meant turning the history of rock and roll into a study of two key years, 1965 and 1966, and limiting my civil rights research to a single campaign. Much better to go deep than go wide.

- Be prepared to invest in your work, but do it wisely. Obtaining new information can often be done via telephone or email, but it often is necessary to go to the source, which can mean travel and accommodations expenses. While researching Selma, I learned to carefully plan my visits to Alabama ahead of time. I scheduled interviews ahead of time, made lists of the places I wanted to see, contacted library and museum employees in advance to enlist their help, and plotted travel routes for maximum efficiency. Also be prepared to pay substantial sums of money for photo publication rights and permission to use other copyrighted material, such as song lyrics.

- Be thorough. I frequently obtained useful information during casual conversation at the end of formal interviews, or by checking with one or two more sources even after I thought I had what I needed. This extra research might yield some facts that significantly alter the narrative or simply serve to add color and detail to your work. Either way, it’s worth it.

- Document everything. The first order of nonfiction, of course, is to get it right. While it is said that newspaper reporters write the first rough draft of history, nonfiction authors must present a definitive history. If their work is to withstand the rest of time, it must be accurate. In writing Selma, I made copies of every newspaper article, every investigative report and every court transcript I reviewed. I also recorded every interview, whether conducted in person or over the phone. Those copies and recordings were invaluable as I sought to accurately reflect what I had learned. Personal note: Although many states allow telephone conversations to be recorded without the source’s knowledge, I consider it good practice and common decency to first seek permission.

Be alert for telling details. When describing something or someone, it pays to make note of the little things that will help bring your story to life. Paint a picture for the reader, but again, make sure you get it right. Relying on memory, I described a key source in Selma as “tall and slender,” and was dismayed to discover during a post-publication meeting that he was in fact of average height and slightly overweight. No big deal, perhaps, but it shouldn’t have happened, and it shows how easy it is to get something wrong.

Keep meticulous records of your reference material and other sources. When it is time to compile your endnotes, you will be lost unless you have a detailed account of where you obtained every bit of information included in the book. And don’t forget to adjust the end notes accordingly when you edit and rearrange your manuscript. Do this as you proceed. As I discovered the hard way, it’s no fun trying to retroactively match source and information once you fall behind.

That’s what I know. Not as sexy as writing a best-selling novel, perhaps, but very rewarding nevertheless.

-AWP-